Biblio

Walter Hang's letter to NYS DEC Commissioner Grannis regarding 270 pollution releases. For a critique (12/18/2009) of Mr. Hang's claims, see the Oil and Gas Industry-funded Energy In Depth website's article. See also the Sourcewatch web page critiquing Energy in Depth.

"...I write today because I do not believe your response refutes the fact that the 270 uncontrolled pollution releases document serious regulatory shortcomings. I also will dispute your belief that gas and oil problems are “promptly and effectively addressed."

All of the 270 oil and gas releases I identified in November were documented in DEC’s hazardous materials spills database.

I subsequently learned the spills database does not include natural gas problems reported to health authorities in the three counties with the highest number of oil and gas wells in New York State. I also learned DEC’s Division of Mineral Resources does not report all oil and gas releases to the Division of Spills.

I write today to document dozens of additional natural gas concerns that have neither been fully investigated nor remediated. These incidents reinforce grave concerns about the adequacy of DEC’s gas drilling regulations and provide further documentation that the draft SGEIS is inadequate and must be withdrawn."...

Very truly yours,

Walter Hang

215 North Cayuga Street

Ithaca, NY 14850

Cc: Honorable Judith Enck, US EPA Region 2 Administrator

Honorable Michael Bloomberg, Mayor, City of New York

Honorable Barbara Lifton, Representative, 125th Assembly District

Honorable William Parment, Representative, 150th Assembly District

Honorable James Gennaro, City Council Member, District 24

Like many villages in China’s industrial heartland, Qiugang — a hamlet of nearly 1,900 people in Anhui province — has long suffered from runaway pollution from nearby factories.

In Qiugang’s case, three major enterprises with little or no pollution controls churned out chemicals, pesticides, and dyes, turning the local river black, killing fish and wildlife, and filling the air with foul fumes that burned residents’ eyes and throats and sickened children.

This exclusive e360 video report, “The Warriors of Qiugang” — co-produced by Yale Environment 360 — tells the story of how the villagers fought to transform their environment, and, in the process, found themselves transformed as well.

The 39-minute video focuses on an unlikely hero — farmer Zhang Gongli, now almost 60, who leads the village’s fight to shut down the chemical plant. Soft-spoken and easy-going, but with a backbone of steel, Zhang — who has only a middle-school education — quickly learns how to use China’s more stringent federal environmental laws to put pressure on the factory owners and their cronies in local and regional government.

“We are sorry to be born in this place,” says Zhang, “but we had no choice. This was forced upon us.”

The camera follows Zhang as he deals with threats from local thugs, rallies his neighbors, and travels to Beijing, where he attends a heady meeting of China’s emerging environmental movement. Zhang — like so many other Chinese — finds himself plunged into a new and wholly unfamiliar world.

The Warriors of Qiugang, was nominated for a 2011 Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject).

See: A Life’s Value May Depend on the Agency, but It’s Rising

The New York-based Toxics Targeting went through the Department of Environmental Conservation’s own database of hazardous substances spills over the past thirty years.

They found 270 cases documenting fires, explosions, wastewater spills, well contamination and ecological damage related to gas drilling.

Derrick Ek. "Gas drilling concerns aired at DEC hearing," Nov 19, 2009. Corning Leader.

Ithaca environmental activist Walter Hang details a history of problems caused by the oil and gas industry in New York State.

Much of the focus on the rapid expansion of natural gas extraction through hydrofracturing, or “fracking,” has centered on methane leaks and chemical contamination of residential water wells. In Dimock, Pa., more than 15 residents sued Cabot Oil and Gas Corp., charging permanent damage to their wells.

However, another concern is the impact of fracking on renewable sources of fresh water. Some fear that this drilling process may be draining valuable and irreplaceable water resources.

See: Do the natural gas industry’s surface water withdrawals pose a health risk?

"The West Virginia coalfields contain some of the highest quality water in the world. Aquifers in the coalfields often sit directly below seams of coal. When the coal seam is undisturbed, it acts as a giant carbon filter, leaving excellent water quality that West Virginians across the state rely on for drinking water.

When coal seams are disrupted, however, water quality quickly declines. The accounts of impaired water quality in the coalfields are abundant. As mining continues and practices such as slurry injections and impoundment sites become more prevalent, communities are seeing a decline in their water quality.

One woman from Hopkins Fork had her water tested when she moved into her home in 2002 and was told it was of spring water quality, as good as any you could buy. Today, she does not even use the water to brush her teeth...

...In total, several hundred million gallons of coal slurry were injected underground within 3 miles of the nearest well user. Some residents suspect that the heavy blasting at the Black Castle Surface mine cracked the geologic layers allowing the coal slurry to enter the water table.

Environmental Engineer Dr. Scott Simonton agrees this is a plausible scenario. Despite repeated requests by residents and citizens groups, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection still refuses to study the water in Prenter to determine the source of the contamination."

Aurora Lights supports locally-based projects that strengthen the connections within and between human communities and their natural environment by promoting environmental and social action. See also: Aurora Lights Home.

The Clean Water Act is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Commonly abbreviated as the CWA, the act established the goals of eliminating releases to water of high amounts of toxic substances, eliminating additional water pollution by 1985, and ensuring that surface waters would meet standards necessary for human sports and recreation by 1983.

The Clean Water Act is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Commonly abbreviated as the CWA, the act established the goals of eliminating releases to water of high amounts of toxic substances, eliminating additional water pollution by 1985, and ensuring that surface waters would meet standards necessary for human sports and recreation by 1983.

The principal body of law currently in effect is based on the Federal Water Pollution Control Amendments of 1972, which significantly expanded and strengthened earlier legislation. Major amendments were enacted in the Clean Water Act of 1977 and the Water Quality Act of 1987.

Please note that information taken from Wikipedia should be verified using other, more reliable sources. It is a good place to start research, but because anyone can edit Wikipedia, we do not recommend using it in research papers or to obtain highly reliable information.

"TakePart.com is an independent online community that connects its members directly to the issues that inspire them to engage, contribute and take action. Our team of editors, writers, and researchers curate and deliver actions in context with in-depth primers to the social, environmental, political and cultural issues of our day.

Our growing global community includes citizens, activists, and large and small non-profits. We invite local and community groups to interact, explore issues, share resources, develop campaigns and use our platform to promote the causes they care most about."

Abrahm Lustgarten

Gas drilling companies such as Halliburton say the gas drilling technique known as hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," is safe, but opponents contend it pollutes groundwater with dangerous substances. Now, new evidence has emerged possibly linking natural gas drilling to groundwater contamination.

ProPublica journalist Abrahm Lustgarten reports federal officials in Wyoming have found that at least three water wells contain chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing.

Abrahm Lustgarten is a former staff writer and contributor for Fortune, and has written for Salon, Esquire, the Washington Post and the New York Times since receiving his master's in journalism from Columbia University in 2003.

More than three decades after the Clean Water Act, iconic American waterways like the Chesapeake Bay and Puget Sound are in perilous condition and facing new sources of contamination.

With polluted runoff still flowing in from industry, agriculture and massive suburban development, scientists note that many new pollutants and toxins from modern everyday life are already being found in the drinking water of millions of people across the country and pose a threat to fish, wildlife and, potentially, human health.

In Poisoned Waters, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Hedrick Smith examines the growing hazards to human health and the ecosystem...

...In addition to assessing the scope of America's polluted-water problem, Poisoned Waters highlights several cases in which grassroots citizens' groups succeeded in effecting environmental change: In South Park, Wash., incensed residents pushed for better cleanup of PCB contamination that remained from an old asphalt plant. In Loudon County, Va., residents prevented a large-scale housing development that would have overwhelmed already-strained stormwater systems believed to contribute to the contamination in Chesapeake Bay.

See Credits.

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA 1974) is the principal federal law in the United States that ensures safe drinking water for the public. Pursuant to the act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is required to set standards for drinking water quality and oversee all states, localities, and water suppliers who implement these standards.

SDWA applies to every public water system in the United States. There are currently more than 160,000 public water systems providing water to almost all Americans at some time in their lives. The Act does not cover private wells.

In 1996, Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act amendments to emphasize sound science and risk-based standard setting, small water supply system flexibility and technical assistance, community-empowered source water assessment and protection, public right-to-know, and water system infrastructure assistance through a multi-billion-dollar state revolving loan fund. They were signed into law by President Bill Clinton on August 6, 1996.

See: Safe Drinking Water Act 101 | Online Training | Drinking Water Academy

Please note that information taken from Wikipedia should be verified using other, more reliable sources. It is a good place to start research, but because anyone can edit Wikipedia, we do not recommend using it in research papers or to obtain highly reliable information.

The quality of drinking water is an urgent concern for over forty million people who live in proximity to the Marcellus Shale.

"The 35-year-old federal law regulating tap water is so out of date that the water Americans drink can pose what scientists say are serious health risks — and still be legal.

Only 91 contaminants are regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act, yet more than 60,000 chemicals are used within the United States, according to Environmental Protection Agency estimates. Government and independent scientists have scrutinized thousands of those chemicals in recent decades, and identified hundreds associated with a risk of cancer and other diseases at small concentrations in drinking water, according to an analysis of government records by The New York Times.

But not one chemical has been added to the list of those regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act since 2000.

Other recent studies have found that even some chemicals regulated by that law pose risks at much smaller concentrations than previously known. However, many of the act’s standards for those chemicals have not been updated since the 1980s, and some remain essentially unchanged since the law was passed in 1974."

February 02, 2010. Cleveland Plain Dealer.

A drilling technique that is beginning to unlock staggering quantities of natural gas underneath Appalachia also yields a troubling byproduct: powerfully briny wastewater that can kill fish and give tap water a foul taste and odor.

With fortunes, water quality and cheap energy hanging in the balance, exploration companies, scientists and entrepreneurs are scrambling for an economical way to recycle the wastewater.

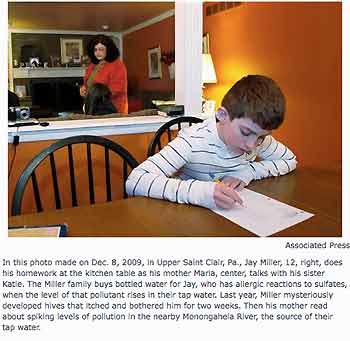

The Miller family buys bottled water for Jay, who has allergic reactions to sulfates, when the level of that pollutant rises in their tap water. Last year, Miller mysteriously developed hives that itched and bothered him for two weeks. Then his mother read about spiking levels of pollution in the nearby Monongahela River, the source of their tap water.

See: Urbina, Ian. “Regulation Is Lax for Water From Gas Wells.” The New York Times 26 Feb. 2011. Web. 27 Feb. 2011.

See: With Natural Gas Drilling Boom, Pennsylvania Faces an Onslaught of Wastewater

See: Do the natural gas industry’s surface water withdrawals pose a health risk?

The estimated population of Pulteney is about 1,300.

At times Sunday it looked like every one of them was crowded into the Pulteney Fire Hall to discuss the proposed plan to deposit contaminated wastewater in a former natural gas well.

More than 300 people came to hear a panel discuss the plan. Chesapeake Energy approached Pulteney officials last fall about the plan to dump the wastewater, which is generated from the hydrofracking process, into a well about a mile west of Keuka Lake.

Jim Robbins. September 10, 2006. New York Times.

It is a strange fight, Montana ranchers say. Raising cattle here in the parched American outback of eastern Montana and Wyoming has always been a battle to find enough water.

Now there is more than enough water, but the wrong kind, they say, and they are fighting to keep it out of the river.

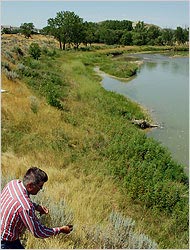

Mark Fix is a family rancher whose cattle operation depends on water from the Tongue River. Mr. Fix diverts about 2,000 gallons per minute of clear water in the summer to transform a dry river bottom into several emerald green fields of alfalfa, an oasis on dry rangeland. Three crops of hay each year enable him to cut it, bale it and feed it to his cattle during the long winter.

“Water means a guaranteed hay crop,” Mr. Fix said.

But the search for a type of natural gas called coal bed methane has come to this part of the world in a big way. The gas is found in subterranean coal, and companies are pumping water out of the coal and stripping the gas mixed with it. Once the gas is out, the huge volumes of water become waste in a region that gets less than 12 inches of rain a year.

Mark Fix, a cattle rancher in eastern Montana, diverts about 2,000 gallons per minute of Tongue River water in the summer to grow hay for his livestock. But increased sodium in the water could endanger his hayfields.

See: Molly Ivins. (2004) C-Span Book TV Oct. 2, 2004. Bushwacked: Life in George W. Bush's America. Chapter: "Dick, Dubya, and Wyoming Methane." (152)