Contains the keyword press

Cap-and-trade is deader than dead. Everyone in Washington officialdom knows that. Virtually no one in Washington officialdom understands how it would work or how much economists think it would cost, but they're certain it's bad, bad, bad and had to die.

Polluting industries and wealthy right-wing oligarchs, aided by a well-funded grassroots army, sympathetic conservative politicos, and a major cable TV news network, cast cap-and-trade as a plague of socialist cooties that would destroy the economy. The left's Purist Brigade wove florid tales of corruption and plutocracy. The reality -- a long, opaque, technocratic bill burdened with several high-profile side deals -- inspired no one. All the passion, all the anger, was found on the side of opponents.

4) The BP Gulf oil spill kills energy reform

5) The U.N. climate process saves itself

About Grist

You know how some people make lemonade out of lemons? At Grist, we're making lemonade out of looming climate apocalypse.

It's more fun than it sounds, trust us!

Grist has been dishing out environmental news and commentary with a wry twist since 1999 -- which, to be frank, was way before most people cared about such things. Now that green is in every headline and on every store shelf (bamboo hair gel, anyone?), Grist is the one site you can count on to help you make sense of it all.

Each day, we use our Clarity-o-Meter to draw out the real meaning behind green stories, and to connect big issues like climate change to daily life. We count on our users to bring their stories to the table, too -- through blogs, photos, and whatever else they care to share. Except Jell-O molds. Those things scare us.

Grist Staff Bio

David Roberts, Staff Writer

droberts@grist.org

206.876.2020 ext. 220

David was born and raised in the South. A revelatory summer working in Yellowstone National Park convinced him that it was not the world but just the part where he lived that sucked, so he moved out West. After several wayward years spent snowboarding and getting an MA in philosophy (go griz), he woke up with nothing but a dissertation between him and an arid, cloistered life spent debating minutiae with the world's other 12 Dewey scholars. So he bailed. A period was spent trudging through the swamp of Seattle tech work, wading past Amazon.com, IMDb.com, and Microsoft, before the fine folks at Grist fell for his devastating good looks in December 2003.

Several million gallons of "frack" fluid for each well return to the surface as a heavy brine, far saltier than seawater. Disposal of these new volumes of brine is a challenge.

So far, well operators or their agents have been hauling most of the frack flowback to Ohio for underground injection, according to Peterson, because salt removal is expensive and only two Class II, or brine disposal, wells were permitted by West Virginia's Underground Injection Control program.

Now, though, nine commercial brine disposal injection wells are permitted, and seven are operating. Several more are in the permitting pipeline.

The DEP has not in the past required well operators to report their water management in detail.

See: Desalination of Oil Field Brine

See: Gas wells' leftovers may wash into Ohio | Columbus Dispatch Politics

"Of the 84,000 chemicals in commercial use in the United States -- from flame retardants in furniture to household cleaners -- nearly 20 percent are secret, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, their names and physical properties guarded from consumers and virtually all public officials under a little-known federal provision."

February 02, 2010. Cleveland Plain Dealer.

A drilling technique that is beginning to unlock staggering quantities of natural gas underneath Appalachia also yields a troubling byproduct: powerfully briny wastewater that can kill fish and give tap water a foul taste and odor.

With fortunes, water quality and cheap energy hanging in the balance, exploration companies, scientists and entrepreneurs are scrambling for an economical way to recycle the wastewater.

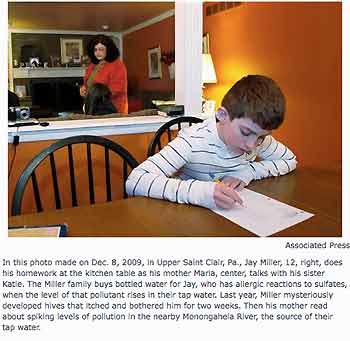

The Miller family buys bottled water for Jay, who has allergic reactions to sulfates, when the level of that pollutant rises in their tap water. Last year, Miller mysteriously developed hives that itched and bothered him for two weeks. Then his mother read about spiking levels of pollution in the nearby Monongahela River, the source of their tap water.

See: Urbina, Ian. “Regulation Is Lax for Water From Gas Wells.” The New York Times 26 Feb. 2011. Web. 27 Feb. 2011.

See: With Natural Gas Drilling Boom, Pennsylvania Faces an Onslaught of Wastewater

See: Do the natural gas industry’s surface water withdrawals pose a health risk?

The estimated population of Pulteney is about 1,300.

At times Sunday it looked like every one of them was crowded into the Pulteney Fire Hall to discuss the proposed plan to deposit contaminated wastewater in a former natural gas well.

More than 300 people came to hear a panel discuss the plan. Chesapeake Energy approached Pulteney officials last fall about the plan to dump the wastewater, which is generated from the hydrofracking process, into a well about a mile west of Keuka Lake.

Thousands of the nation’s largest water polluters are outside the Clean Water Act’s reach because the Supreme Court has left uncertain which waterways are protected by that law, according to interviews with regulators.

As a result, some businesses are declaring that the law no longer applies to them. And pollution rates are rising.

Companies that have spilled oil, carcinogens and dangerous bacteria into lakes, rivers and other waters are not being prosecuted, according to Environmental Protection Agency regulators working on those cases, who estimate that more than 1,500 major pollution investigations have been discontinued or shelved in the last four years.

The Clean Water Act was intended to end dangerous water pollution by regulating every major polluter. But today, regulators may be unable to prosecute as many as half of the nation’s largest known polluters because officials lack jurisdiction or because proving jurisdiction would be overwhelmingly difficult or time consuming, according to midlevel officials.

“We are, in essence, shutting down our Clean Water programs in some states,” said Douglas F. Mundrick, an E.P.A. lawyer in Atlanta. “This is a huge step backward. When companies figure out the cops can’t operate, they start remembering how much cheaper it is to just dump stuff in a nearby creek.”

See: PBS Frontline: "Poisoned Waters"

See Video report: "Supreme Court Restricts Clean Water Act". | Mixplex

See: Kid's view of a local water-quality problem

Students in the Atlanta and Columbus, Ga. area formed The River Kids Network, which tests and cleans up local streams (wearing gloves and boots, of course). Is there an organization in your area that does similar work?

Here are some 3rd graders' observations during a recent creek cleanup:

Not safe, even for bugs

"It's not looking so good. Raw sewage is in the Chattahoochee River, and not many critters can survive there. If bugs can't survive in there, what are humans going to do?"

Just a little effort

"I would just like the river to be clean enough so I could splash around and maybe drink some water. It wouldn't be very hard to make a difference."

Had it up to here

"The problem is that there are sewage leaks going to the creek and the creek goes into the big river. Everyone should help. If everyone helped, you could see right down to the bottom of the creek."

Out from under cover

"I want to play in the creek and not have to wear gloves and boots."

Signs of life are few

"On our monthly trips, we've found a lot of trash, including more than 18 tires, a radio, shoes and plastic bags. We've only found a few forms of life. We saw one turtle and a few bugs, but not many fish."

Jane Park.

Interview with blogger Elizabeth Berkowitz.

Cindy Kalbach and her husband have lived in Gaines for 10 years, enjoying the quiet wilderness. But that's become a lot harder because of increasing drilling activity. With wells as close as a mile away, trucks from gas companies are ravaging their roads, kicking up dust, driving away wildlife and keeping the Kalbachs indoors. Kalbach refuses to lease her land to gas companies, but some of her neighbors haven't been able to resist the offers. People around here are very low income. They just want to live here in peace, you know? And that's a lot of money to them. they don't realize what they're getting into,said Kalbach. Kalbach took her concerns to Elizabeth Berkowitz, an avid blogger who started Faces of Frackland to give a voice to people who feel like no one is listening.

WASHINGTON COUNTY, PA - At first, farmer Ron Gulla and horse farm owner Joyce Mitchell were excited about the prospect of making money from gas drilling. Now, after more than two years of the presence of drilling companies with their heavy trucks and huge drill rigs, they and many of their neighbors wish they had never signed a lease.

Gasses bubbling out of the ground and into drinking wells and ponds. Before drilling is begun, a landowner should have the water tested for baseline items, he said. “The only problem is that such tests can be very costly.”

AUSTIN — Democratic gubernatorial nominee Bill White earned more than $2.6 million serving on the board of a gas well servicing company that now is part of a congressional investigation into possible groundwater contamination.

White, who made cleaning Houston's polluted air a hallmark of his tenure as Houston's mayor, has been on the board of BJ Services Co. since 2003, the year he was elected, earning more than $627,000.

White also received almost $830,000 in stock and another $245,000 in stock options. He will receive an additional $180,000 in stock and a retirement payout of $783,000 if the firm's merger with Baker Hughes is approved by shareholders Friday.

The issue of White's involvement with BJ Services came to light after he refused a Houston Chronicle request for his tax returns during his tenure as mayor. The relationship was disclosed in personal financial disclosure statements. White's campaign provided details on his BJ Services earnings Tuesday.

The U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee is investigating Houston-based BJ Services Co., Halliburton and several other oil field service companies to see if the gas extraction method known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a hazard to groundwater drinking supplies in Texas, Arkansas, Colorado, New York, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania.